Understanding Attitudes Toward LGBT People as Victims of Crimes

New study on the attitudes towards LGBT people as victims of crimes

Piotr Godzisz (PhD) is the Principal Investigator in the project Call It Hate. He sits on the Management Board of Lambda Warsaw, the Polish LGBT support organisation, and the Advisory Board of the International Network for Hate Studies. He’s recently been appointed to the position of Lecturer in Criminology at the Birmingham City University.

Lead

Not long ago we published a blog on the expectations of the model hate crime victim written by Dr Caroline Erentzen. This week we are returning to this important topic. Focusing on the attitudes towards LGBT victims in Europe, Dr Piotr Godzisz presents key findings of the 10-country survey conducted as part of the international research project Call It Hate: Raising Awareness of Anti-LGBT Hate Crime. Following the overview of the results, recommendations for policymakers on how to approach anti-LGBT hate crime are offered.

Introduction

Of the groups affected by hate crime, LGBT people often fall short of the image of ideal victims. A myriad of reasons may cause this: Public displays of sexual and gender diversity may be viewed as immoral, while some attacks may take place in or around night-time economy venues, such as gay bars, when victims are intoxicated. On the offender side, the opposition to the “LGBT ideology” – e.g. through blocking Pride events – may be framed as a legitimate way of protecting the society (particularly children) from harm.

Conversely, however, some characteristics of anti-LGBT hate crime lend credibility to the victims. Particularly those perceived as vulnerable, or weaker than the offender, e.g. women and children, should be likely to garner sympathy more readily than others. Hate crime offenders, on the other hand, may be portrayed by the media as dangerous extremists, a threat to the stability of the society.

With the above set of seemingly opposing characteristics, LGBT victims of crimes could be the “ideal object” of studies on model (or “ideal”) victims, blame attribution, and support for hate crime laws. Nonetheless, there is surprisingly little hard evidence available to feed into academic or policy discussions. Building on the characteristics of the ideal victim proposed by Christie (1986), the Call It Hate research set out to respond to the gaps in the knowledge by measuring the observers’ reactions to anti-LGBT victimisation. A set of scenarios has been developed to probe whether a hierarchy of victimhood exists in respect to LGBT victims of crime and whether the respondents engaged in any forms of victim blaming. The study further develops the field by measuring the likelihood of intervention on behalf of victims, as well as measuring the support for various strands of hate crime laws in all 10 countries.

Methodology

The Call It Hate survey was carried out by an international consortium of polling agencies led by Kantar Poland, on behalf of, and under the supervision of, Lambda Warsaw, the Polish LGBT organisation. Representative samples of populations in 10 EU countries: Belgium, Bulgaria, Croatia, Hungary, Ireland, Italy, Lithuania, Poland, Slovenia, and the United Kingdom (the total of 10,612 people) participated in the research, making it the largest public opinion poll on the attitudes towards LGBT people as victims of crime ever conducted.

In all countries, the survey included questions about lesbians, gay men and transgender people. These results are presented below. Additionally, the Irish and the UK versions included questions about bisexual people.

Selected results

Empathy for victims

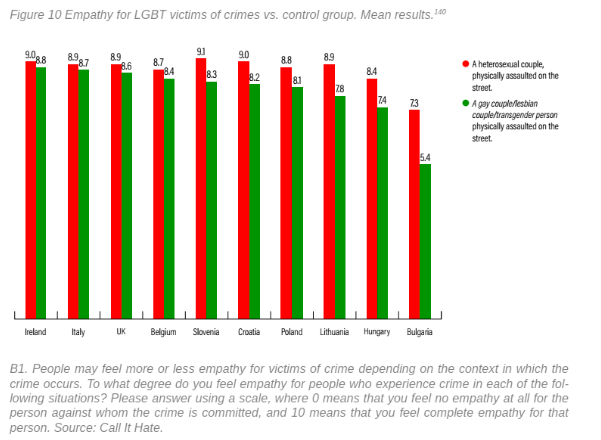

The survey found that the level of empathy (i.e., the capacity to understand or feel what another person is experiencing) for victims of crimes depends on the victims’ sexual orientation. In all 10 countries, a heterosexual couple assaulted on the street for holding hands received significantly more empathy from respondents than a same-sex couple in a comparable situation.

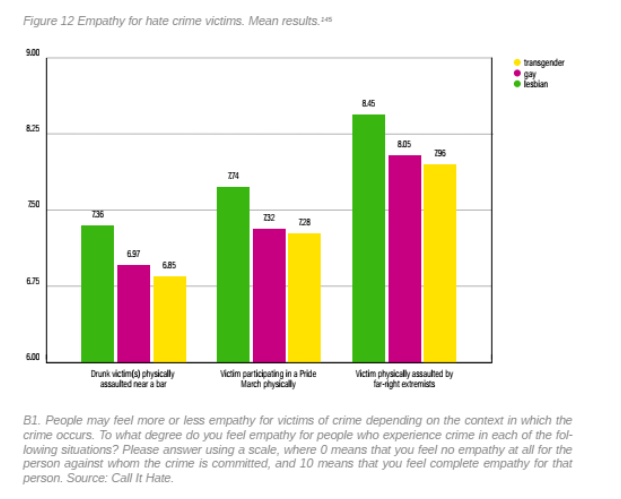

The level of empathy for lesbian, gay and transgender victims also depended on the context of the attack. Particularly, victims assaulted during Pride events or when drunk near bars, as well as transgender sex workers, evoked less empathy than other victims. The level of empathy was additionally affected by the gender and the gender identity of victims (lesbians received more, and transgender victims received less empathy than others) and the type of offender (more empathy if the offender is stronger than the victim).

Reactions

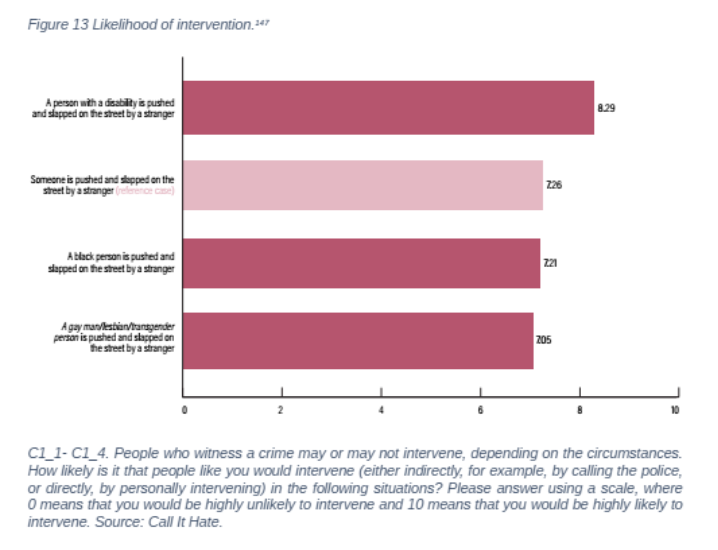

The survey found that the characteristics of the victim impacted the probability of witnesses reacting to the crime (e.g., by calling the police). En bloc, the survey found that a lesbian, gay or transgender person was less likely to receive help than a person with a disability, a black person or an undescribed “someone” used as a reference case.

When victim categories are disaggregated, people were more willing to intervene on behalf of lesbians (as women) than gay men or transgender people.

There was a strong correlation between the means for reaction to an assault on lesbians, gay men or transgender people and the means for empathy towards people belonging to these categories when they are attacked.

Opinions on hate crime

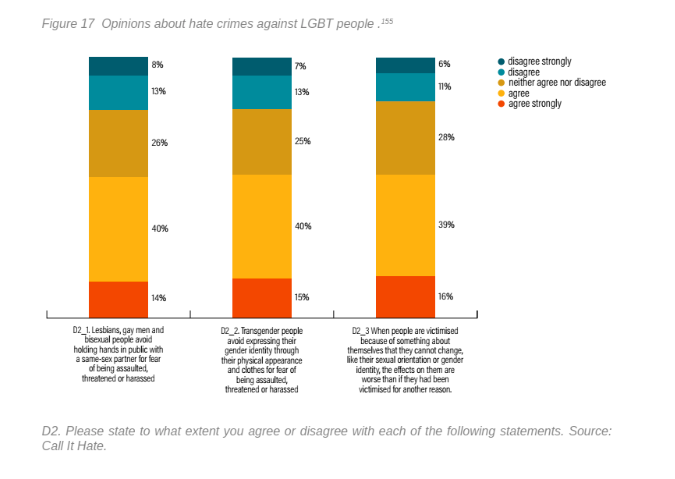

The survey found that over half of the respondents in the sample believed that lesbians, gay men, bisexual people and transgender people change their behaviour or appearance in public for fear of being assaulted, threatened or harassed.

55 per cent of respondents believed that when people are victimised because of something about themselves that they cannot change, like their sexual orientation or gender identity, the effects on them are worse than if they had been victimised for another reason.

Sentencing

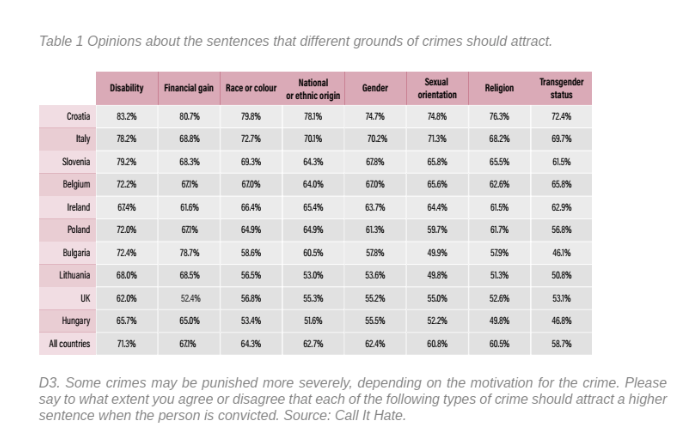

The results of the survey show that 71.3 per cent of the respondents in the 10 polled countries agreed that hate crimes targeting people because of their disability should be punished more severely. Six out of ten respondents (60.8 per cent) believed that crimes motivated by bias based on sexual orientation should be punished more severely.

The results however, seem to show general view that sentences for crimes should be higher rather than specific support for penalty top-ups in hate crime cases: The support for higher sentences in the reference case (a common crime with a financial motive) was at the level of 67.1 per cent, which is the second most popular result, after the motive based on disability.

Conclusions and recommendations

The survey paints a rather grim picture of Europe. We find evidence of a hierarchy of victimhood wherein the “blameworthiness” of victims of crimes is evaluated in determining their “deservedness”. Victims are perceived – and judged – differently because of their characteristics, the characteristics of the offenders, as well as the context of the crime. LGBT people as victims of crimes receive – en bloc – less empathy than other victims, are less likely to get help from bystanders, and the homophobic or transphobic motivation of a crime is less often seen as an aggravating circumstance deserving a top-up in penalty. Transgender people seem to be the most disadvantaged – not just in terms of empathy, but also in support for gender identity being treated as a protected characteristic in hate crime laws. These findings align well with Christie’s (1986) observations on the ideal victim.

Considering the level of awareness of anti-LGBT hate crime, the results show that respondents – regardless of the country – have relatively little knowledge about the consequences of hate crime for members of the targeted communities. Perhaps this explains why the support for higher penalties for sexual orientation and (particularly) gender identity hate crime is lower (although still above 50 per cent) than for crimes motivated by financial gain.

Considering the probability of reaction to violence, there is a significant number of people who claim that they are willing to intervene on behalf of the victims. While this is reassuring, the practice shows that the numbers of reported anti-LGBT hate crime cases in most countries (with the exception of the UK) remain low, while many victims feel left alone and unsupported. There is a need to rectify this situation and empower people who declare readiness to turn their declarations into actions. This research suggests how this conversion can be achieved. Possible campaigns, publicly funded and organised in partnership with civil society, should focus on increasing empathy for victims – e.g. through building understanding of hate crime and its consequences and reducing the stigma and social distance. There is a role here for both the EU and the national governments, who should take all necessary steps to address bias violence, including through adoption of comprehensive legal and policy frameworks on hate crime and victims’ rights.

The full Call It Hate research report, edited by Dr Piotr Godzisz and Dr Giacomo Viggiani and consisting of 10 country chapters and one comparative chapter, is available for download from the project website, along with other resources for researchers, professionals and victims of hate crime.

***

The project Call it Hate is implemented in 10 EU Member States and co-funded by the European Commission through the Rights, Equality and Citizenship programme 2014-2020. The International Network for Hate Studies is an associate partner in the project.