How come ‘intolerant’ Poland is among European leaders in collecting data on hate crimes?

By Piotr Godzisz. Piotr is a doctoral student at UCL’s School of Slavonic and East European Studies, and a graduate of the Faculty of Journalism and Political Science, University of Warsaw. His research examines the development of national hate crime policies in Europe. As part of a project supported by the UCL European Institute’s Junior Research Forum, he has drafted the working paper Forgotten Friends: ODIHR and Civil Society in the Struggle to Counter Hate Crime in Poland. An early version of this blog was originally published in the Comments section at UCL European Institute’s website.

In Poland over the past ten years, there has been a creeping recognition of the need to combat hate crime. While intolerance remains an issue in this Central European country, developments in in the official response to targeted violence, especially in data collection, are evident. Nevertheless, it is still not clear what motivated the authorities to address this issue. Piotr Godzisz explores what explains Poland’s leadership in this regard.

Over the last ten years, Poland’s response to hate crime has improved. But while the developments are visible, it is unclear what exactly motivates the government to address this issue or, in other words, where the pressures come from. In the United States of America and the United Kingdom, changes in the official response to hate crimes, including enacting legislation and setting up structures to capture data, were mostly driven by advocacy groups. In continental Europe, however, efforts of civil society organizations are backed up by another type of actor – supranational, intergovernmental organisations, which, in some cases, provided the necessary leverage.

Based on an analysis of documents related to the legislative process, reports to international organisations, as well as interviews with Polish and international officials and activists conducted between December 2014 and November 2015 in Poland and Belgium, one could describe the role of international organisations in developing national hate crime measures in the following two ways:

Data collection and reporting

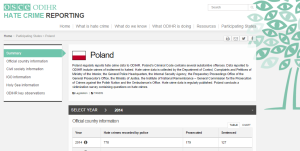

Firstly, Poland’s approach to recording data on hate crime has greatly improved over the past ten years. From 194 cases recorded by the police in 2009 to 778 recorded in 2014, the state has improved its ability to capture data on racist and xenophobic crimes. But this is not all: the Government monitors, records and reports on hate crimes targeting people because of their sexual orientation, gender identity and disability, which are currently not included in the Criminal Code’s list of protected grounds. As a result of the improvements in the data collection mechanisms, Poland is among European leaders in this category. For example, it is one of only nine (out of 57) OSCE countries to collect data and report on crimes targeting LGBT people.

The change in the data collection mechanisms can be linked to pressure coming from supranational bodies. International institutions, such as the UN treaty bodies, the European Commission Against Racism and Intolerance, and the EU Fundamental Rights Agency require Poland to collect hate crime data. Indeed, most public officials interviewed as part of this research indicated that the obligation to report was the primary reason for the improvement.

Legislation

Secondly, despite on-going debates, Polish legislation related to hate speech or targeted violence has not changed. As a result, victims of homophobic, transphobic and disablist crimes are not protected by hate crime laws, as victims of racially- and religiously-motivated crimes are (see also the report by Amnesty International). The lack of progress in this area can be linked to the fact that the bulk of the efforts were carried out by civil society organisations. Although they were effective enough to put the issue on the parliamentary agenda, they lacked the leverage necessary to convince the Ministry of Justice to support the draft amendments (see also here).

Synergy effect

In this context, an effective strategy that has been employed is co-operation between advocacy groups and supranational bodies, aimed at amplifying civil society demands. In seeking support for the change of law, NGOs have turned to IGOs, using methods such as shadow reports. As a result, IGOs, in their recommendations for Poland, started to stress the need to amend the Criminal Code by including sexual orientation, gender identity and disability in the catalogue of protected grounds. Ten years after the beginning of advocacy efforts, their authority has contributed to transforming the “ignorable” demands of minority groups into subjects of international queries (similarly to data collection) which are not as easy to ignore by a Government that cares about its international reputation. As a result, just before the end of the term of Parliament in October 2015, the Polish Government expressed a willingness to expand the catalogue of protected grounds, quoting international recommendations as a reason for doing it.