A new Hate Crime Act is needed to address vast ‘justice gap’ for hate crime in England and Wales

By Dr Mark Walters, co-Director of the International Network for Hate Studies

It is almost twenty years since the UK Government enacted specific race hate crime offences (ss. 28-32 Crime and Disorder Act 1998 (CDA)). Since then, the legislation has been amended to include religious-based hate crimes, while sentencing provisions that prescribe sexual orientation, disability and transgender hostilities have also been introduced (as set out in the Criminal Justice Act 2003 (CJA)). The piecemeal way in which hate crime laws have been enacted in the United Kingdom means that there are now different levels of legislative protection for the current five recognised groups commonly targeted for hate crime. In response to this, in 2012, the Ministry of Justice requested that the Law Commission examine whether the Government should extend the aggravated offences in the CDA (England and wales only) to apply equally to all five protected characteristics. In its final 2014 report, the Commission recommended that a wider review of the law be carried out in order to determine how the law should be amended, abolished or extended.

In response to the Commission’s report, the University of Sussex recently conducted a 24 month study on the application of hate crime laws in England and Wales, which was funded by the EU Directorate-General Justice and Consumers department as part of a wider European study on hate crime legislation across five EU member states (England and Wales; Ireland; Sweden; Latvia; and the Czech Republic). A mixed-methods approach was employed for the project which enabled us to compare and contrast the stated aims and purposes of policies and legislation with the experiences of those tasked with enforcing and applying the law. This approach included: (a) an assessment of existing policies and publically available statistics; (b) a review of over 100 reported cases; and (c) 71 in-depth, qualitative semi-structured interviews with “hate crime coordinators” and “hate crime leads” at the Crown Prosecution Service (CPS), District (Magistrates’ Court) and Circuit (Crown Court) Judges, independent barristers, victims and staff at charitable organisations that support victims of hate crime, police officers, and local authority minority group liaison staff.

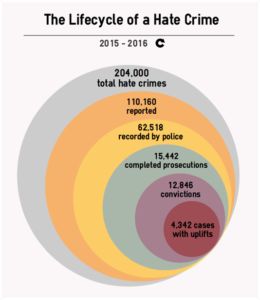

Using publically available statistics and new data analyses provided by the ONS for us on hate crime, we calculated an approximate number of offences that are likely to “drop out” of the criminal justice system. The total number of cases that drop out of the system represent what is known as the “justice gap” for hate crime. Analysis of the Crime Survey for England and Wales (CSEW) suggests that between 2015-16 approximately 110,160 hate crimes were reported to the police. Yet official police statistics for the same period recorded just 62,518 hate crimes. This suggests that only 57% of those incidents reported to the police are recorded as hate crimes. During the same year, the CPS prosecuted 15,442 hate-based offences, of which 12,846 resulted in a conviction. The CPS also recorded the announcement of sentencing uplifts in court as 33.8% of total hate crime convictions, which equates to 4,342 cases. If these data are accurate, it means that out of an approximate 110,160 reported hate crimes, only 4,342 offences (4%) resulted in a sentence uplift based on identity-based hostility. In other words, approximately 96% of reported hate crimes (102,658 cases) may not result in a sentence uplift.

There are a number of possible reasons for this significant “justice gap” for hate crime, including: differences in definitions of hate crime used by the police compared with the courts; diverging dates between reporting and legal action; victims retracting statements; and perpetrators never being apprehended (amongst various other factors). However, we also identified a number of factors that restrict the successful application of hate crime legislation within the legal process for hate crime that are likely to exacerbate the rate of attrition for hate crimes. During our study we identified the following problems:

- A systemic failure to identity and “flag” disability hate crimes, as well as a reluctance amongst many judges and legal practitioners to accept evidence of targeted violence against disabled people as proof of “disability hostility”;

- A general lack of awareness of ss. 145 & 146 of the Criminal Justice Act 2003 amongst certain key professionals, indicating that disability, sexual orientation and transgender-based hate crimes are less likely to attract a sentence uplift;

- A reluctance in parts of the judiciary to accept “demonstrations of hostility” committed in the “heat of the moment” as falling within the scope of the legislation;

- A perceived reluctance amongst jurors to accept “demonstrations of hostility” committed in the “heat of the moment” as falling within the scope of the legislation;

- The potential for “double convictions” in the Magistrates’ Courts, where defendants are convicted for both the basic and aggravated version of the offence (though only punished once);

- Diverging approaches to calculating “uplifts” for enhanced sentencing, with calculated uplifts ranging from 20%-100%;

- A general lack of use of rehabilitation or community-based sanctions for hate crime offenders.

The study concludes that hate crime laws are still too frequently ignored or incorrectly applied by the courts. Without legal reform, along with amendments to procedure and new options for alternative justice, we believe that many victims and defendants will be denied justice. In order to address these perceived problems within the legal process for hate crime we advocate four key law reform options:

- We recommend, as a minimum, that Parliament amend s. 28 of the Crime and Disorder Act 1998 to include sexual orientation, disability and transgender identity.

- Based on the statistics and analysis of interviewee data, the following offences should be considered for inclusion under the CDA: Affray; Violent disorder; All sexual offences; Theft and handling stolen goods; Robbery; Burglary; Fraud and forgery; S. 18 Grievous bodily harm; Homicide offences

- The Government should legislate to create a new Hate Crime Act that consolidates the existing fragmented framework which would prescribe any offence as “aggravated” in law where there is evidence of racial, religious, sexual orientation, disability and/or transgender identity hostility. Sentencing maxima for the aggravated offences should be the same as for the basic offence, with the legislation mirroring ss. 145 and 146 CJA in so far as the courts “must” take into consideration hostility (or the by reason selection, explained below) and state in open court how the sentence has been affected by the aggravation.

- We propose that the successful prosecution of all types of hate crime will be enhanced were the legislation to be amended at s. 28(1)(b) (or equivalent in a new Hate Crime Act) so that the provision now reads as follows: “the offence is committed by reason of the victim’s membership (or presumed membership) of a racial or religious group, or by reason of the victim’s sexual orientation (or presumed sexual orientation), disability (or presumed disability), or transgender identity (or presumed transgender identity).”

If these options for reform are taken up by the Government, we strongly believe that the criminal justice system will be better equipped to tackle the growing problems associated with hate crime in England and Wales.

Further analysis and recommendations can be found in the full report (including an executive summary): “Hate Crime and the Legal Process: options for law reform”

The report is co-authored by Mark A. Walters, Susann Wiedlitzka and Abenaa Owusu-Bempah, with Kay Goodall.

Pingback: A new Hate Crime Act is needed to address vast ‘justice gap’ for hate crime in England and Wales – LaPSe of Reason

Good afternoon. I am interested as to how you know that there were 204,000 hate crimes in 15-16 rather than hate incidents some ( maybe many) of which would subsequently be categorised as crimes..best wishes

Hullo. I would be grateful if one of the researchers involved in the research which includes the graphic “lifecycle of a hate crime” could answer my question: namely , how can you define something as a hate crime rather than a hate incident before it has been reported, as per the graphic?

Apologies, I didn’t see these comments before. A hate crime is a criminal offence (such as an assault) which is perceived by the victim or anyone else to be motivated by prejudice or hostility based on one of the five protected characteristics. A hate incident is a non-crime incident (such as verbal abuse, taunting someone etc) which is perceived to be motivated by hate or prejudice. The Life Cycle infographs include crimes only, so the number of “hate incidents” would be much much higher. Hope that helps. Mark